V for Vendetta is in the awkward position of being a film that was maligned by its original creator, the incomparable Alan Moore. And while I have deep respect for Moore as a writer, I can’t help but disagree with his criticism of this film.

Especially now. Not after the massacre that has occurred in Orlando, Florida.

A note before we begin. V for Vendetta is a political tale no matter how you cut it. It is also a tale of great personal importance to me, both for its impact when it came out and in light of recent events. With that in mind, this piece is more political and personal than the previous two, and I ask that everyone keep that in mind and be respectful.

Alan Moore’s experience with the film adaptations of From Hell and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen had soured him on Hollywood’s reworking of his stories. His complaints about V for Vendetta centered around a few points, the first being that producer Joel Silver had stated in an interview that Moore had met with Lana Wachowski, and was impressed with her ideas for the script. According to Moore, no such meeting took place, and when Warner Brothers refused to retract the statement, Moore broke off his relationship with DC Comics for good. His other irritation had to do with the alteration of his political message; the graphic novel was a dialogue about fascism versus anarchy. The Wachowskis’s script changed the central political themes so that they more directly aligned with the current political climate, making the film more of a direct analog to American politics at the time.

Moore deplored the change to “American neo-liberalism versus American neo-conservativism,” stating that the Wachowskis were too timid to come right out with their political message and set the film in America. He also was aggravated that the British government in the film made no mention of white supremacism, which he felt was important in a portrayal of a fascist government. As a result, he refused his fee and credit, and the cast and crew of the film held press conferences to specifically discuss the changes made to the story. (David Lloyd, the co-creator and artist of the graphic novel, said that he thought the film was good, and that Moore likely would have only been happy with an exact comic-to-film adaptation.)

Two things. To start, Alan Moore’s particular opinions of how art and politics should intersect are his own. I respect them, but I don’t think it’s right to impose them on others. There are many reasons the Wachowskis might have decided not to set the film in the United States–they might have felt it was disrespectful to the story to move it, they might have felt that the analog was too on-the-nose that way. There are endless possibilities. Either way, their relative “timidity” for setting the film in England doesn’t seem relevant when all is said and done. As for the alterations to the narrative, they make the film different from Moore’s tale, of course–which is an incredible story in its own right, and a fascinating commentary on its era–but they work to create their own excellent vision of how these events might unfold. (I also feel the need to point out that though no mentions of racial purity are made, we only see people of color at Larkhill detention centre, which seems a fairly pointed message in terms of white supremacism.) V for Vendetta is a film that has managed to get more poignant over time, rather than less, which is an achievement in its own right.

In addition, while many of the political machinations may have seemed to apply to American politics at the time, that wasn’t the sole intention of the film. Director James McTeigue was quick in interviews to point out that while the society they depicted had much in common with certain America institutions, they were meant to serve as analogs for anywhere with similar practices–he stated explicitly that while the audience might see Fox News in the Norsefire Party news station BTN, it could easily be Sky News over in the UK, or any other numbers of venues that were like-minded.

Much of the moral ambiguity inherent in the original version was stripped away, but a great deal of the dialogue was taken verbatim nonetheless, including some of Moore’s best lines. The Wachowskis’s script focused even more on the struggle of the queer population under the Norsefire Party, which was startling to see in a film like this even ten years ago–and still is today, if we’re being frank. Gordon Deitrich, Stephen Fry’s character, is altered entirely into a talk show host who invites Natalie Portman’s Evey to his home under false pretenses at the start of the film–because he has to hide the fact that he is a gay man. The V in this film is a far more romantic figure than the comic makes him out to be, Evey is older, and also pointedly not a sex worker, which is a change that I was always grateful for (there are plenty of other ways to show how horrible the world is, and the film does just fine at communicating that). You could argue that some of these changes create that Hollywood-ization effect that we so often mourn, but to be fair, giving an audience a crash course in anarchy and how it should oppose fascism–in a story where no one is a definitive hero–would have been a tall order for a two-hour film.

Fans have always been divided on this movie. It has plotholes, sure. It’s flawed, as most movies are. It’s different from its progenitor. But it’s a film that creates divisive opinions precisely because it provokes us. It confronts us. And it does so using the trappings of a very different sort of film, the sort you would normally get from a superhero yarn. The Wachowskis tend to gravitate toward these sorts of heroes, the ones who are super in everything but the basic trappings and the flashy titles. The fact that V has more in common with Zorro or Edmond Dantes than he does with Batman or Thor doesn’t change the alignment. And the fact that V prefers to think of himself as an idea rather than a person speaks very specifically to a precise aspect of superhero mythos–at what point does a truly influential hero go beyond mere mortality? What makes symbols and ideas out of us?

Like all stories that the Wachowskis tackle, the question of rebirth and taking strength from confidence in one’s own identity is central to the narrative. With V portrayed in a more heroic light, his torture (both physical and psychological) of Evey–where he gets her to believe that she has been imprisoned by the government for her knowledge of his whereabouts–is perhaps easier to forgive despite how horrific his actions are. What he does is wrong from a personal standpoint, but this is not a story about simple transitions and revelations. Essentially, V creates a crucible for someone who is trapped by their own fear–an emotion that we all want liberation from, the most paralyzing of all. Evey is unable to live honestly, to achieve any amount of personal freedom, to break away from a painful past. The entire film is about how fear numbs us, how it turns us against one another, how it leads to despair and self-enslavement.

The possibility of trans themes in V for Vendetta are borne out clearly in Evey and V’s respective transformations. For Evey, a harrowing physical ordeal where she is repeatedly told that she is insignificant and alone leads to an elevation of consciousness. She comes out the other side a completely different person–later telling V that she ran into an old coworker who looked her in the eye and couldn’t recognize her. On V’s side, when Evey tries to remove his mask, he tells her that the flesh underneath that mask, the body that he possesses, is not truly him. While this speaks to V’s desire to move beyond mortal man and embody an idea, it is also true that his body is something that was taken from him, brutalized and used by the people at Larkhill. Having had his physical form reduced to the status of “experiment,” V no longer identifies with his body. More importantly, once he expresses this, Evey never attempts to remove his mask again, respecting his right to appear as he wishes to be seen.

That is the majority of my critical analysis regarding this film. At any other time, I might have gone on at length about its intricacies.

But today is different, and I can’t pretend that it is not.

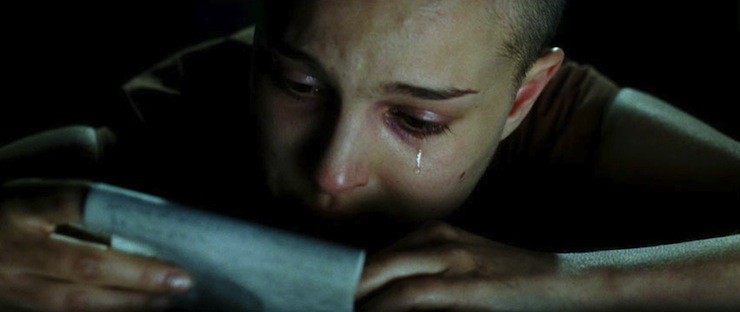

Talking about this film in a removed fashion is a trial for me most days of the week because it occupies a specific place in my life. I saw it before I read the graphic novel, at a time before I had completely come to terms with being queer. And as is true for most people in my position, fear was at the center of that denial. The idea of integrating that identity into my sense of self was alarming; it was alien. I wasn’t sure that I belonged well enough to affirm it, or even that I wanted to. Then I went to see this film, and Evey read Valerie’s letter, the same one that V found in his cell at Larkhill–one that detailed her life as a lesbian before, during, and after the rise of the Norsefire Party. After her lover Ruth is taken away, Valerie is also captured and taken to Larkhill, experimented on, and ultimately dies. Before she completes this testament to her life written out on toilet paper, she says:

It seems strange that my life should end in such a terrible place. But for three years I had roses, and apologized to no one.

I was sobbing and I didn’t know why. I couldn’t stop.

It took time to figure it out. It took time to come to terms with it, to say it out loud, to rid myself of that fear. To talk about it, to write about it, to live it. To watch the country that I live in take baby steps forward, and then huge leaps backward. My marriage is legal, it’s Pride Month, the city that I live in is full of love and wants everyone to use whatever bathroom works best for them.

And then this weekend, an angry man walked into a gay club in Orlando and killed 50 people.

But for three years I had roses, and apologized to no one.

I know why I’m sobbing now. I can’t stop.

And I think about this film and how Roger Allam’s pundit character Lewis Prothero, “The Voice of England,” tears down Muslims and homosexuals in the same hateful breath, about how Gordon Deitrich is murdered not for the uncensored sketch on his show or for being gay, but because he had a copy of the Qur’an in his home. I think about the little girl in the coke bottle glasses who gets murdered by the police for wearing a mask and spray painting a wall, and I think about how their country has closed its border to all immigrants.

Then I think about a man who is running for President who used Orlando as a reason to say “I told you so.” To turn us against each other. To feel more powerful. To empower others who feel the same way.

And I think about this film, and the erasure of the victims at Larkhill, locked up for any difference than made them a “threat” to the state. Too foreign, too brown, too opinionated, too queer.

Then I think about the fact that my wife was followed down the street today by a man who was shouting about evil lesbians, and how ungodly people should burn in fires. I think about the rainbow wristband my wife bought in solidarity today but decided not to wear–because it’s better to be safe right now than it is to stand tall and make yourself a target.

And I think about the fact that this film is for Americans and for everyone, and the fact that it still didn’t contain the themes of the original graphic novel, and I dare you to tell me that it doesn’t matter today. That we don’t need it. That we shouldn’t remember it and learn from it.

We need these reminders, at this exact moment in time: Do not let your leaders make you afraid of your neighbors. Do not be complacent in the demonization of others through inaction. Do not let your fear (of the other, of the past, of being seen) dictate your actions. Find your voice. Act on behalf of those with less power than you. Fight.

And above all, love. Love your neighbors and strangers and people who are different from you in every conceivable way. Love art and mystery and ideas. Remember that it is the only truly triumphant response to hate.

I don’t think I needed a reminder of why this film was important to me, but today… today it hurts even more than the first time I saw it. A visceral reminder of my own revelation, all wrapped up in a tale about a man wearing a Guy Fawkes mask who wanted governments to be afraid of their people, who wanted revenge on anyone who would dare hurt others for being different. A tale of a woman who was reborn with a new capacity for love and a lack of fear, who read Valerie’s last words in a prison cell and gained strength from them:

I hope that the world turns and that things get better. But what I hope most of all is that you understand what I mean when I tell you that even though I do not know you, and even though I may never meet you, laugh with you, cry with you, or kiss you. I love you. With all my heart, I love you.

The most empowering words of all.

Emmet Asher-Perrin wishes everyone a safe Pride, full of all the love they deserve. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.